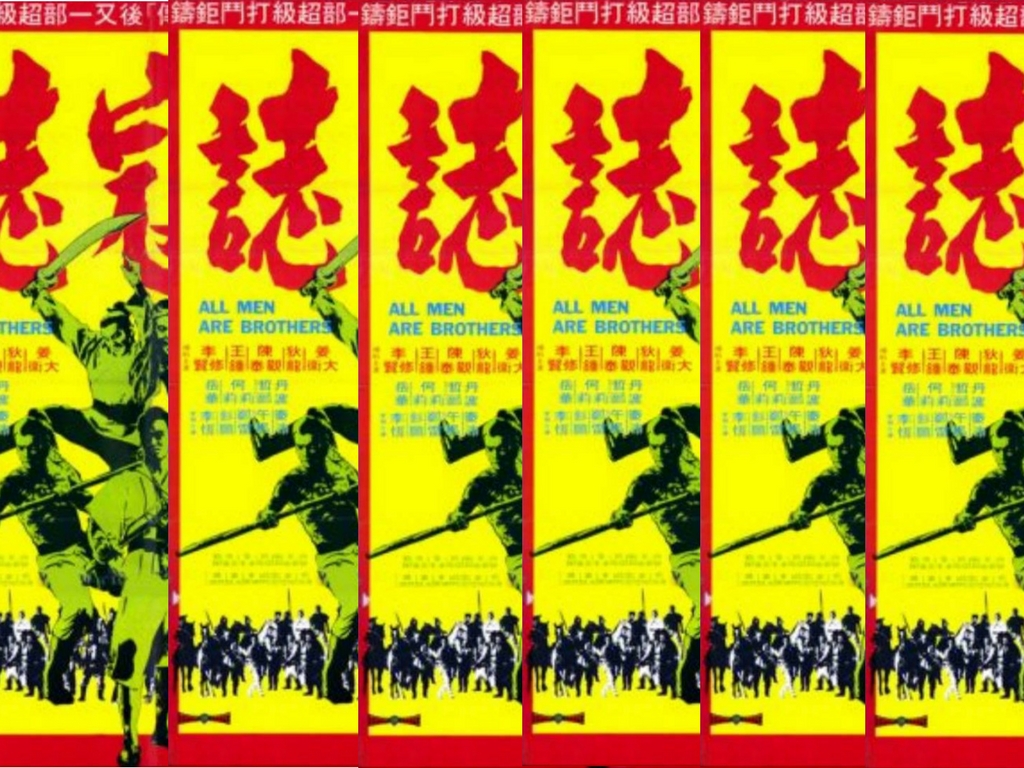

07 May ALL MEN ARE BROTHERS (1975) REVIEW

By Will Kouf of Silver Emulsion Film Reviews

===

All of the Shaw Brothers films based on the classic Chinese novel Outlaws of the Marsh (AKA The Water Margin) are among my all-time favorites. The best of the bunch is probably The Water Margin, but the one that nearly surpasses it is All Men Are Brothers. The previous films dealt with chapters from either the beginning or the middle of the book, but All Men Are Brothers seeks to tell the end of the tale. It takes material mostly from Chapters 90-100 (out of 100 total chapters), which deal with the redemption of the outlaws through their struggle to defeat the rebellious Fang La and his generals. A couple of flashbacks tell earlier tales to provide some character depth, and the film opens with Yan Qing’s procurement of the bandits’ pardon from the emperor (which is detailed in Chapter 81), but the film is mostly concerned with bringing everything to a close.

While none of this specifically matters to your enjoyment of the film, it does speak to the immense task of adapting the novel to film. It is a massive book with literally hundreds of distinct characters, so to have whittled it down into a manageable series of films is impressive. Reading the adapted chapters is an interesting experience, as well, since the novel only vaguely resembles what we know as a novel these days. It tells a story, but it does so without guiding us through every emotion and occurrence that befalls our heroes. One line in the book could translate to an entire scene in some cases, and in many instances, there are wide gaps that need to be filled if the movie is to make any sense. Specifically, battles are very briefly covered, where All Men Are Brothers (and martial arts films in general) derives much of its intrigue and suspense through these action-packed situations.

All Men Are Brothers could work as a standalone film, but it is immeasurably more impressive after viewing all the Shaw Brothers Water Margin films (The Water Margin, The Delightful Forest, Pursuit, and for added context the 1964 Huangmei opera The Amorous Lotus Pan), as each previous tale provides backstory that informs and enriches the overall experience. This brilliant cycle of films proves once again why Chang Cheh and Ni Kuang were such a skilled and formidable screenwriting duo. Writing is so often an unsung job in kung fu films, but their work here, which keeps the spirit of the novel alive even when they must go forth on their own, is nothing short of brilliant. In addition, the amount of details from the novel that are worked in is equally impressive. All Men Are Brothers is the only film in the series that shows our outlaw heroes cohesive and on the offensive, a benefit of adapting the novel’s final chapters. The prior films dealt with how various characters came to be affiliated with the Liang Shan bandits, but All Men Are Brothers is the story of how they reclaimed their status as righteous men fighting for the good of their country. As such, it’s a film absolutely filled to the brim with action, intrigue, and thrills. I love every one of the films in this series, but All Men Are Brothers is easily the most flat-out fun.

The plentiful action is choreographed by the four-man team responsible for The Water Margin: Lau Kar-Leung, Tang Chia, Lau Kar-Wing and Chan Chuen. They do exceptional work in the film, making each battle unique and entertaining in its own right. They also do an outstanding job at incorporating some incredible fountains of blood and gore into the proceedings. By no other metric than my internal “Gore Meter,” I honestly think that All Men Are Brothers is the goriest Shaw Brothers film up to this point. It’s really something to behold (provided you enjoy Shaw gore). This is also apparently what held back the film’s release for two-three years, as the Hong Kong censors’ crackdown on gore forced the delay. I don’t know if the final film was edited in any way to secure its eventual 1975 release, but if so then it REALLY must have been over the top in terms of gore, because the released version is absolutely brimming with gore and blood. I did see mention in other reviews that certain scenes of violence were tinted red during the original release (similar to Heroes Two), but thankfully this imposition is not represented in Celestial’s remastered edition.

Given what I know of Chang Cheh’s co-directed films, it is fairly safe to assume that All Men Are Brothers was entirely (or almost entirely) directed by Wu Ma. It bears the pseudo-Chang Cheh style used by his proteges (Pao Hsueh-Li and Wu Ma), which I generally describe as the style of the Chang Cheh of a few years prior (like 1970-1971) without a specific artistic intent. Looking at The Water Margin, Chang Cheh’s aesthetics were at a different place at the time of this film’s production (most likely 1972), and his films are generally more emotionally involved, artistically bold (with touches like the anachronistic music that The Water Margin bears) and “epic” (for lack of a better word). But Wu Ma’s style is perfectly suited to this men-on-a-mission tale involving the Liang Shan bandits, and I honestly couldn’t think of a single thing that could’ve been better about it. It’s a more straightforward film, but it works perfectly for the story being told.

All Men Are Brothers is a perfect sequel to The Water Margin that moves to its own rhythm, delivering an experience previously untouched in the series. My only complaint is that they didn’t make more Water Margin films!

===

Stream All Men Are Brothers on Amazon Prime here!